FRANKLIN – After 16 years of convincing landowners to give up development rights on their property, Sharon Fouts Taylor is putting her money – and her land – where her mouth is.

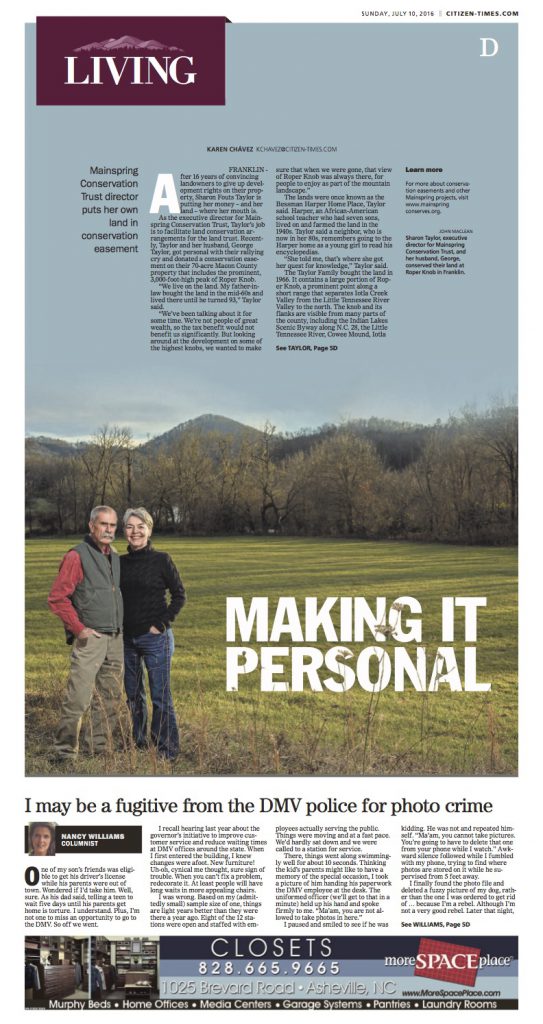

As the executive director for Mainspring Conservation Trust, Taylor’s job is to facilitate land conservation arrangements for the land trust. Recently, Taylor and her husband, George Taylor, got personal with their rallying cry and donated a conservation easement on their 70-acre Macon County property that includes the prominent, 3,000-foot-high peak of Roper Knob.

“We live on the land. My father-in-law bought the land in the mid-60s and lived there until he turned 93,” Taylor said.

“We’ve been talking about it for some time. We’re not people of great wealth, so the tax benefit would not benefit us significantly. But looking around at the development on some of the highest knobs, we wanted to make sure that when we were gone, that view of Roper Knob was always there, for people to enjoy as part of the mountain landscape.”

The lands were once known as the Bessman Harper Home Place, Taylor said. Harper, an African-American school teacher who had seven sons, lived on and farmed the land in the 1940s. Taylor said a neighbor, who is now in her 80s, remembers going to the Harper home as a young girl to read his encyclopedias.

“She told me, that’s where she got her quest for knowledge,” Taylor said.

The Taylor Family bought the land in 1966. It contains a large portion of Roper Knob, a prominent point along a short range that separates Iotla Creek Valley from the Little Tennessee River Valley to the north. The knob and its flanks are visible from many parts of the county, including the Indian Lakes Scenic Byway along N.C. 28, the Little Tennessee River, Cowee Mound, Iotla Valley, and Nantahala National Forest lands.

George Taylor, recently retired as a technician with the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, was well aware of the great biodiversity on the land and wanted to make sure the land always remained as a haven for plants and wildlife. The property includes rich cove, acidic cove, Mesic oak-hickory, pine-oak heath forests, and a white pine plantation, as well open fields managed for wildlife.

This diversity is attractive to a wide range of wildlife, including whitetail deer, black bear, coyote, bobcat, gray fox, red fox, turkey, grouse, and numerous other bird species. The Taylor property also contains more than 105 species of plants.

About 475 feet of perennial stream flows through the tract, and feeds into another first-order stream, which flows directly into the Little Tennessee River. This part of the Little Tennessee is designated as a Significant Natural Heritage Area by the N.C. Natural Heritage Program and as U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service occupied Critical Habitat for the federally endangered Appalachian elktoe mussel and the federally threatened spotfin chub.

The forested upper flanks of Roper Knob also serve as a protective watershed for many other streams that flow off the peak.

“George and I always hoped we could protect Roper Knob as part of our legacy,” said Sharon. “While I’ve had countless conversations with families as they considered and realized their dreams of conserving their own family land, it wasn’t until a few years ago that George and I started thinking seriously about the impact we could forever make.”

The Conservation Trust for North Carolina provided Mainspring a $13,800 grant to help with transaction costs of the easement. A conservation easement is a voluntary legal agreement between a landowner and a land trust or government agency that permanently limits uses of the land to protect its conservation values. Conservation easements protect land for future generations while allowing owners to retain many private property rights and to live on and use their land.

The Taylors retained the right to farm and harvest timber but gave up the right to construct other houses on the property.

As the executive director of Mainspring, Taylor said she is passionate about conserving land, but was surprised to find herself struggling with the decision to “give up” the value of the land for development.

Sharon’s family has lived in Macon County for multiple generations. George grew up in Florida, but finished school in Franklin. The couple got married right after Sharon graduated from Franklin High School, and have been married for 41 years. They do not have children, but have nieces and nephews that they took into consideration when removing the building rights from their land.

“We work with people all the time who have children. We always encourage people to consider how their children will feel as well,” Sharon said. “I believe people come here because this place is beautiful, and that beauty is part of the mountain economy.”

Mainspring Conservation Trust, which was established in 1997 and changed its name earlier this year from the Land Trust for the Little Tennessee, manages 71 conservation easements totaling more than 10,100 acres. Mainspring serves seven counties: Cherokee, Clay, Graham, Jackson, Macon and Swain in North Carolina, and Rabun County, Georgia. The land trust’s mission is to conserve and restore the lands and waters of the Southern Blue Ridge, and to connect the people to these natural treasures.

Chris Brouwer, chair of the Mainspring board of directors, said all conservation easements are important for land trusts but a land trust director’s personal easement is particularly special, much like the easements placed by Walter Clark, executive director of the Boone-based Blue Ridge Conservancy, over the past decade. Clark protected a total of 81 acres of a working blueberry farm on his land in northwest Ashe County.

“I think it’s especially telling when an executive director makes this type of commitment,” Brouwer said. “Sharon and George’s donation is tangible proof of how much they believe in Mainspring’s mission, longevity, and impact on Western North Carolina and we are forever grateful for the gift they’ve given to all of us.”

Sharon said she hopes her family’s donation will help inspire others to consider saving their land.

“I have always been grateful for the families that have made that important choice, but now I have an even deeper appreciation for their gift to all of us. We’re proud to be included with them and making a personal difference in WNC.”

Photo of Sharon and George Taylor by John MacLean.